News

Ouest France: "ENTRETIEN. " La visio, c'est le mythe du travail qui s'adapte à notre vie... mais c'est l'inverse "" (In French only)

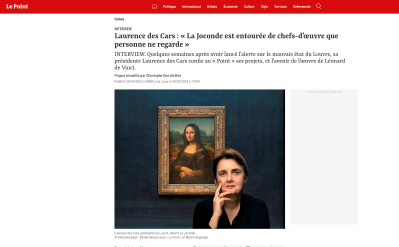

In La Visio m'a tuer, author Alexandre des Isnards tells the story of office life in the age of telecommuting. In some twenty sketches drawn from real-life events, he brilliantly describes our troubled times. Interview.

Alexandre des Isnards, author of "La Visio m'a tuer" | STÉPHANE GEUFROI, OUEST-FRANCE

A WhatsApp group between colleagues where everyone rivals each other in enthusiasm using emojis, a meeting on Teams with colleagues who are just a few meters away from you in the open space, long telecommuting days chaining together visios without moving from your chair... Ten years ago, all this might have sounded like something out of a sci-fi movie, but today, it's a daily reality for millions of people around the world, and perhaps even for you.

And if, fifty or a hundred years from now, historians want to better understand our era, they will find in Alexandre des Isnards' new book, La Visio m'a tuer,

a formidable source of material. Co-author with Thomas Zuber of L'open space m'a tuer in 2011, and Facebook m'a tuer in 2013, the man who likes to describe himself as an "archaeologist of the world of work" is back with the recipe that has made him such a success: twenty or so playlets from office life, drawn from real events, told like short stories that can be savored and reveal a bittersweet flavor in the form of questions about what we've become. Interview.

Telecommuting came into its own during the Covid crisis. But it remained once the confinements were over. How can we explain this?

Without the pandemic, we wouldn't have moved into the world we all know, and which I describe in the book. The technology was already there, but the use didn't exist, because there was a kind of taboo around telecommuting. This taboo was broken with Covid: the crisis showed that it was possible to work remotely, and once the crisis was over it was accepted by company directors and managers, because there was a strong demand from employees. There's no going back, even if telecommuting is regulated and managed. In the end, it was a win-win situation for everyone. Even shareholders, who can save on rents: the size of premises is reduced by switching to flex office.

There's something for everyone, really?

Let's just say that it's in everyone's interest. The employee can do his laundry between meetings, and optimize his personal time during office hours: it's precious... but it comes at a cost. The boundary between private and professional life is gradually disappearing, as in the case of Julien, who decided to join his partner Emma for a weekend in Val d'Orléans, and who set up one videoconference after another in the small Airbnb rented for the occasion. The Wi-Fi allows him to make "calls" with his team... but it spoils his family's vacation. Tracances", a contraction of "work" and "vacation", look good on paper. But in reality, it can quickly become a pain.

An orange on the shift key

And yet, working by the pool sounds pretty appealing, doesn't it?

Yes, it's the myth that work adapts to our lives. But it's the other way around: telecommuting creates a working atmosphere everywhere, all the time. There are no limits. Some people spend the whole day alone at home, chaining video meetings together, without a break. In "TLT" [short for telecommuting, editor's note], we don't give ourselves the right to dawdle, and if we do dawdle, while watching a series or playing video games, or even folding laundry, we hide it. On the other hand, idling in the office is encouraged: chatting with colleagues at the coffee machine, taking a smoke break, it's not frowned upon. I tell the story of Max who goes to the post office to pick up a registered letter, and who, in the meantime, puts an orange on the shift key on his keyboard to keep the Teams indicator light green. There's an internalization of surveillance, which is always stronger than surveillance itself.

Yet the younger generations are very much in favor of teleworking...

Yes, young people love being able to organize their time to suit their personal constraints, and the company has to adapt. Not always easy, as illustrated by the misadventure of Théo, a UX designer who plays it straight and asks for Friday off so he can go surfing "early in the morning and late at night" in Biarritz. His boss, Richard, falls off his chair. And refuses. Théo's reaction: "If they don't trust me, bye-bye, it'll be a pain in the ass. But we shouldn't caricature things either: young people aren't blissful about telecommuting. I also tell the story of a trainee who arrives at the office, and finds himself all alone, because his N + 1 and his whole team are teleworking. His N + 2 is forced to take charge of him, because the team has failed.

Telecommuting puts this collective to the test ...

It forces the company to question itself. Let me take up the anecdote of the employee surfer. I understand Théo's attitude: after all, if the job gets done... Why impose this penance of coming to the office on him and the rest of the team? But if everyone does the same, if everyone exiles themselves to the sun to work, it's the collective that erodes. So I also understand the feeling of the rest of the team, and of their boss. Everyone realizes that if flexibility has no limits, if everyone does as they please, then we're all out of sync. We get up in the morning, we don't know who's going to be in the office, and coming to see colleagues becomes the primary criterion of "face-to-face". So we invent ways of getting back into sync, with links formed elsewhere, virtually, for example in colleagues' WhatsApp groups or aperitifs that can degenerate into "convivial harassment", as for Carla, a supply planner, who finds herself obliged to "drink shots" and talk about her "first time", because "it's customary".

Not easy to find the right balance... No, and it's understandable that companies are shaken. Employees no longer share the same experience. We no longer build for the long term. It used to be that you could "make a career" within a company. If you joined Saint-Gobain, you were safe until you retired. Little by little, employers have stopped offering this: they promise employees to improve their employability, only to sell themselves elsewhere later. There is no longer any long-term investment, because the collective has disintegrated. And when there's no longer a collective, there's a form of dehumanization: candidates disappear during the recruitment process, without warning. It's easier to break up with someone when you don't see them, when you don't meet them. At that point, the risk for a fully remote employee is to be forgotten, or to be fired by video! If we want to create a collective, we have to make sacrifices, on the part of both the company and the employee.

Read the article on www.ouest-france.fr

By Thomas Bronnec

Published May 5, 2024