News

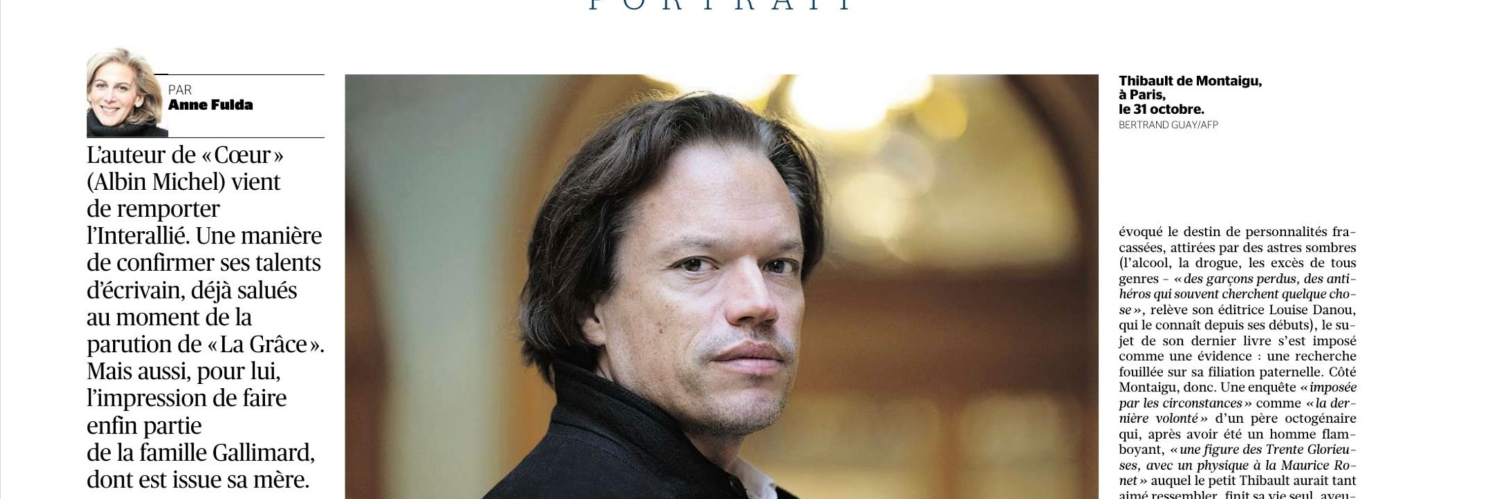

Le Figaro: "Je ne pouvait plus mentir" (I could no longer lie): Thibault de Montaigu, by the grace of his father" (in French)

13 November 2024

Press review

Viewed 3313 times

PORTRAIT : The author of Cœur has just won the Interallié. It's a confirmation of his talent as a writer, already acclaimed at the time of the publication of La Grâce, but also, for him, a sense of...

You must be logged in to read more